France-Germany : a double perspective

The exhibition aims to approach the 1870–1871 war from a twin perspective, both French and German. The conflict and its consequences are explained from the standpoints of the two warring parties, and works by French and German artists as well as objects and documents from both countries illustrate and reinforce this perspective. The museum has developed comprehensive partnerships with a broad range of German museums (the German Historical Museum, the Museum of Prints and Drawings and the Picture Gallery, both part of the Berlin State Museums, and the Old National Gallery), which have contributed generously to the exhibition with many major loans as well as essays and articles published in the catalogue. The works and objects from the German collections will be displayed alongside those from French collections and put into context as part of a museum visit whose key stages have been defined with the help of a scientific committee. The committee is headed by Professor Jean-François Chanet, chancellor of the Besançon Academy, and made up of French and German historians and curators, including Professor Hans Ottomeyer (honorary president of the German Historical Museum), Doctor Thomas Weissbrich (curator at the German Historical Museum), Doctor Mareike König (German Centre for Art History) and Doctor Christine Krüger (University of Giessen).

Paul Hadol, also known as White

Paul Hadol, also known as White

Map of Europe in 1870, after a French Woodcut

[Karte von Europa im Jahre 1870, nach einem französischen Holzschnitte], 1870

German Historical Museum Foundation, Berlin

© Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin/ I. Desnica

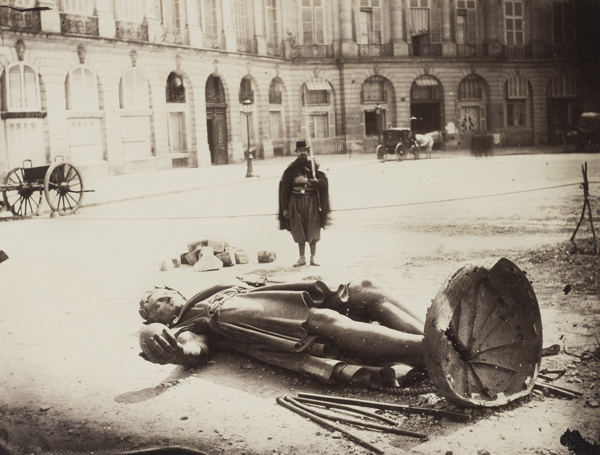

The ‘annus horribilis' as spectacle

The Franco-German war and civil war that followed unfolded beneath the eyes of reporters as well as artists who were commissioned or approved by the General Staff, like Werner and Trübner, politically engaged, like Meissonier and Manet, or dedicated to bearing witness, such as Carpeaux, Corot and Menzel. Photography documented the conquest and occupation as well as their consequences, including repairs made to cities’ defence systems, destruction caused by bombardments, prisoners and reconstructions. Then a recent technique, it served to identify the dead and then the suspects as the Communards went on trial. Although recognition of its use as a military reconnaissance tool was slow to develop – as deplored by Nadar, a balloon pilot during the first siege of Paris – in situ photographic images were used by painters Detaille and Neuville when creating their painted panoramas. These works gained international visibility as they were displayed abroad and as photographic reproductions circulated. Acting both to channel and nourish memories of the conflict, photography, engravings and paintings thus gave enduring form to successive and conflicting interpretations of the war.

A number of these works enjoyed widespread international exposure in Europe and the USA as panoramas were duplicated, exhibitions taken on tour and works reproduced in the form of engravings and photogravures, thus incorporating them into the visual memory of conflicts and civil wars. The Commune anniversaries in 1896 and 1901 triggered the production of a series of drawings, paintings and engravings dedicated to the movement and its repression, until then kept in the dark by official republican historiography and its associated iconography. Artists close to the anarchist movements, such as Luce and Vallotton, sometimes drew inspiration from photographs of the protagonists and events to create works whose accusatory aspect was heightened when the Dreyfus affair came to light.

Croisy Aristide-Onésime

Croisy Aristide-Onésime

L'Armée de la Loire

Paris, musée de l'Armée

© Paris, musée de l’Armée / Emilie Cambier

The two sieges of Paris

After the victory at Sedan and the new French Republic’s decision to continue to fight, Moltke, the Prussian Chief of Staff, focused military efforts on Paris in the hope of capturing the capital and winning the war. From 20 September 1870 to 28 January 1871, up to 400,000 German soldiers laid siege to the capital. Protected by the city’s imposing fortifications, 1,750,000 civilians and 450,000 combatants awaited the enemy’s assault – in vain. Moltke preferred hunger as a weapon rather than inflicting bloody street-fighting on his army. The city’s besieged inhabitants suffered badly during the harsh winter of 1870–1871 and from the shortage of coal and food, although they continued to hope that the French armies would succeed. Starting on 5 January 1871, Paris and its suburbs were subjected to sustained bombardment; the Prussian General Staff was infuriated by Parisian resistance and wanted to force the city to surrender – unsuccessfully. In late January 1871, the situation was desperate and France negotiated an armistice that brought the 132-day siege to an end. The capital received food supplies and escaped German occupation.

Following the popular uprising of 18 March 1871, the French government left Paris for Versailles. Fighting began on 21 mars. On 2 April, the French army seized Courbevoie, while the Federates failed to take Versailles on the 3rd. On 30 April, almost 400 artillery pieces installed on Mont-Valérien and the heights of Saint-Cloud, Meudon and Châtillon began to pound the Issy and Vanves forts, key to Parisian defence in the south-west of the city, and the ramparts of its walled enclosure. The bombardments did not just damage the targets, but also hit the city’s western neighbourhoods. On 21 May, the French army entered Paris, marking the beginning of the Bloody Week when the capital’s neighbourhoods fell one after another. Fighting stopped on 28 May when the last barricades in Belleville were captured.

Mandar and Mugnier

Mandar and Mugnier

Paris 1871, Rue de Bondy, 1871

Musée de l’Armée, Paris

© Paris, musée de l’Armée - Dist. RMN-GP / Emilie Cambier

Never forget

Signs of remembrance of the 1870–1871 combatants are visible in Paris and the surrounding area, revealing themselves to anyone who wants to find them. In the city itself, the Lion of Belfort and Place Denfert-Rochereau pay homage to the capital’s resistance and its commander, while at Champigny-sur-Marne and Le Bourget monuments and ossuaries serve as reminders of the battles they are named after. La Défense business district derives its name from Louis-Ernest Barrias’ sculpture, The Defence of Paris, erected in 1883 and aligned with the Arc de Triomphe to commemorate those who defended the besieged capital. In Berlin, the approaches to the Siegessäule – the Victory Column that commemorates the three wars of German unification – have been repeatedly altered by successive regimes, bearing the traces of a distortion of a part of history whose rejection in the wake of World War II has given way to a calmer and more detached approach. Then there are place names such as Sedanstrasse and Strasse der Pariser Kommune, which call to mind the former partition between the two Berlins, West and East.

Émile Robert

Émile Robert

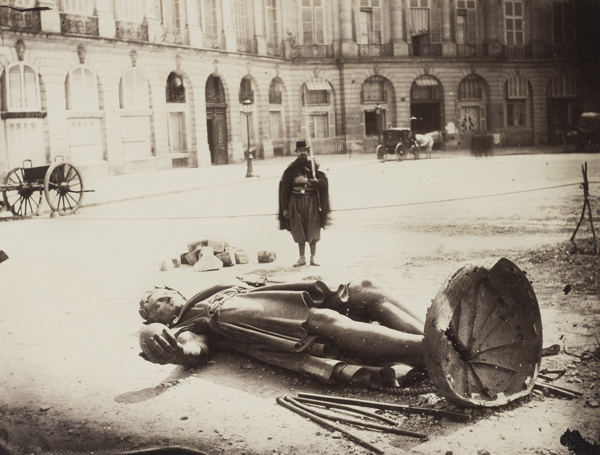

Statue of Napoleon I after the Fall of the Vendome Column, 16 May 1871, 1871

J. Baronnet Collection

© Paris, musée de l’Armée / Pascal Segrette

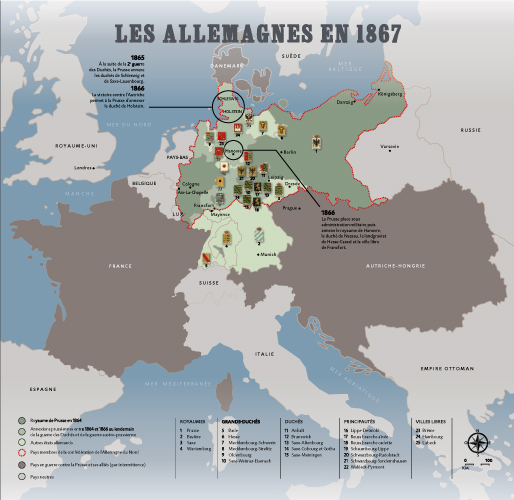

The three wars of german unification

In his determination to unify the German states, Otto von Bismarck engaged Prussia in three wars, known as the ‘wars of unification’.

In 1864, with Austria as its ally, Prussia defeated Denmark: the Danish duchies of Schleswig and Holstein were placed under Prussian and Austrian military supervision respectively.

In 1866, Bismarck accused Austria of managing Holstein ineptly and war was then declared between the two powers. On 3 July 1866, the Prussian armies obtained a decisive victory at Königgrätz and Austria was vanquished. This success halted the construction of a ‘Greater Germany’ centring on Austria and instead established a ‘Little Germany’ under Prussian hegemony. In 1867, the creation of the North German Confederation confirmed this new stage on the path to a unified Germany.

Bismarck then decided that a war against France would constitute the final phase in German unity, despite the reticence of the southern German states. He skilfully manoeuvred Napoleon III into declaring war in July 1870, placing Prussia in the position of wronged party. The defensive alliances established with Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and Hesse stood firm and the armies that entered France in August 1870 were very much ‘German’. Their victories endorsed Bismarck’s policy and, on 18 January 1871, the German Empire was proclaimed at Versailles.

The notion of a triptych of unification wars was ‘invented’ by German historians and journalists in 1871 to demonstrate the inexorability of a unified Germany and glorify its victories.

The commune

A number of Parisians felt that the armistice which brought the 1870–1871 conflict to a close was a betrayal and wanted to pursue the war. In addition, the government took several highly unpopular measures, such as lifting the moratorium on rents and abolishing national guards’ pay. This burst of patriotism, combined with social unrest and the revolutionary tradition, produced a civil war, its start marked by the insurrection of 18 March, with the government headed by Thiers and based at Versailles on one side and the Paris Commune, proclaimed by the Republican Federation of the National Guard, on the other.

For 72 days, the city was run by a commune council, whose programme was partially adopted by the Third Republic, including separation of church and state and free, secular education. Various uprisings also occurred in Lyon, Marseille, Le Creusot and Toulouse, where they were quickly quelled. The government reacted swiftly: the French army laid siege to Paris and fought the federated troops. The city was reconquered as one neighbourhood after another fell. The Germans looked on, and ensured the speedy return of French prisoners of war who swelled the army’s ranks. In the wake of the Bloody Week (21–28 May 1871), the Communards became the target of brutal repression, with arrests, executions, prison sentences and deportation orders to New Caledonia. The Republic granted the Communards an amnesty with two successive laws, in 1879 and 1880. On 29 November 2016, the National Assembly rehabilitated the victims of the repression of the Commune.

Bruno Braquehais

Bruno Braquehais

Barricade on Rue de Castiglione, 1871

Musée de l’Armée, Paris

© Paris, musée de l’Armée, Dist. RMN-GP / Émilie Cambier

Charles Winter

Charles Winter